This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

How to regulate vehicle access in urban areas

This guidance page summarises the learning and cumulated expertise from the European Research & Innovation project CIVITAS ReVeAL.

You may also scroll down to explore the guidance by titles and subtitles: click on the ‘More’ buttons from Unit 2 onwards to open each chapter.

1. Introduction

1.1. About the ReVeAL project

Urban Vehicle Access Regulations (UVARs) are one of the tools that can help make cities more liveable, healthier and more attractive for all, and help support the achievements of some of their goals for transport. The goal of the EU Horizon 2020 project ReVeAL is to support cities producing good practice in UVAR and to add UVARs to the standard range of urban mobility approaches across Europe and beyond.

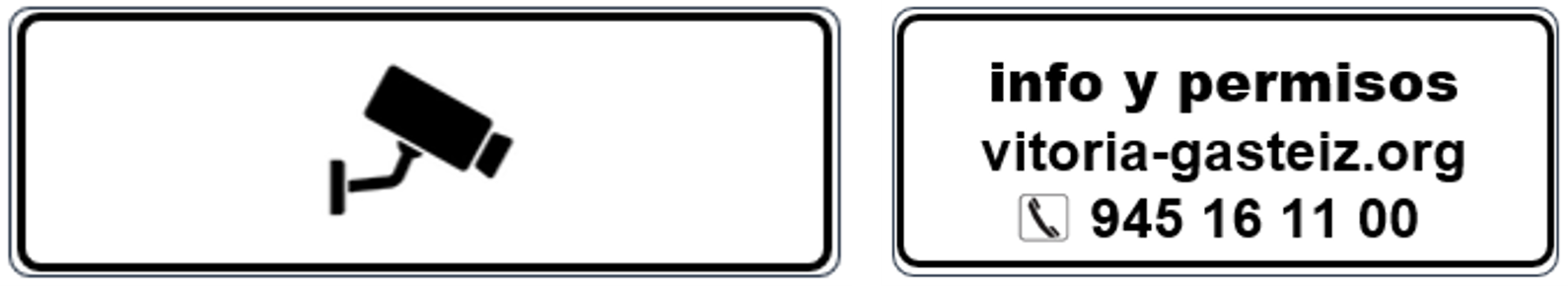

The ReVeAL project supports UVAR implementation in six pilot cities – Bielefeld, Helmond, Jerusalem, Padua, City of London, Vitoria Gasteiz – and has developed a toolkit to help other cities decide what UVARs may be appropriate for them and what to be aware of when implementing, of which this guidance document is part.

To find out more about ReVeAL, please see the ReVeAL website and the ReVeAL UVAR decision support tool.

1.2. What are UVARs?

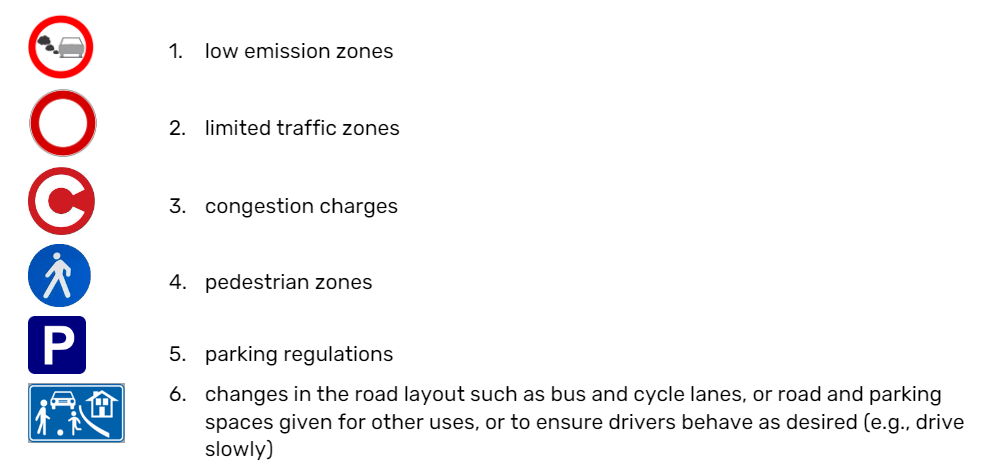

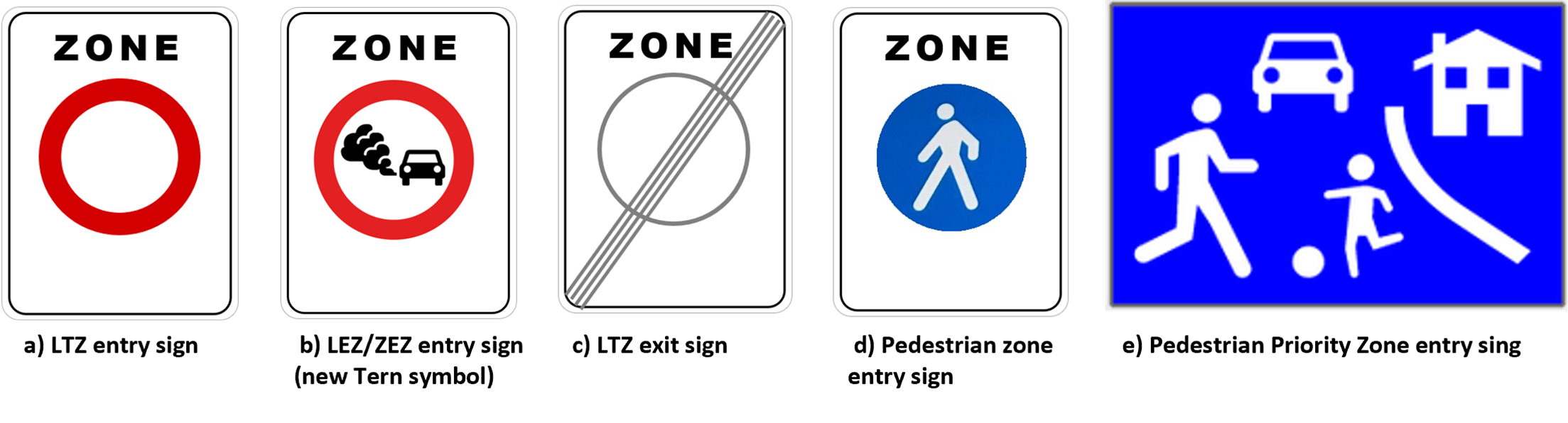

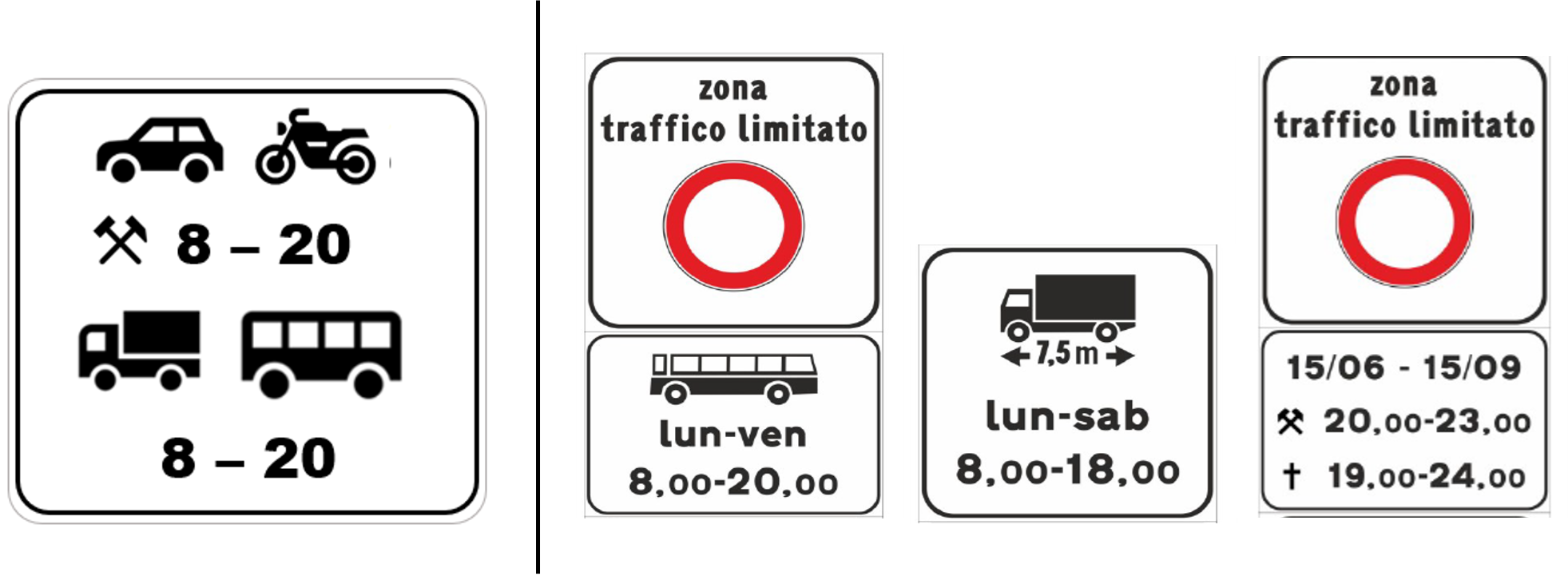

Urban Vehicle Access Regulations are when motorised traffic access is regulated (or restricted). This can be by banning or charging (certain types of) vehicle or behaviour, by taking space away from motorised vehicles to give to sustainable modes or by changing the road layout to ensure that drivers behave as desired. Common types of UVAR include:

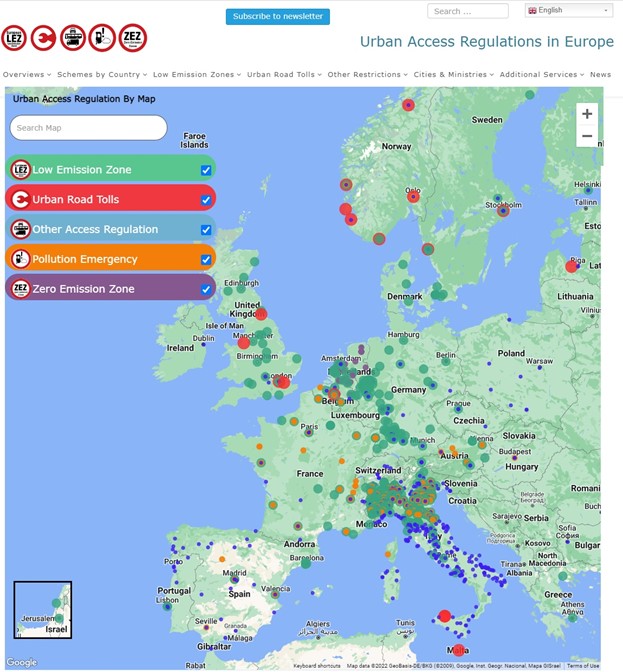

More details on UVARs and their different types will be given later in the document, and an overview of Many of the first three types of UVAR can be found on the website www.urbanaccessregulations.eu (see also Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map of current UVARs across Europe (source: https://urbanaccessregulations.eu)

There are several different definitions of UVAR, some including – or excluding – parking or road layout changes. While the ReVeAL definition includes all of these types, we focus less on parking than on other types as parking is a well-researched field of its own. That said, it could be helpful to consider parking regulations more frequently from a strategic perspective, rather than simply operationally[00].

[00] See the EU project Park4SUMP: https://park4sump.eu/about/objectives

1.3. Why UVAR?

UVARs focus specifically on regulating motor vehicle road traffic, and all references to, for example, congestion, refer to road traffic congestion (as opposed to congestion on the public transport network). There are many valid reasons to implement UVARs to restrict motor vehicle access to urban areas. These include:

- Reducing climate emissions. Road transport is responsible for 15% of greenhouse gas emissions and is reducing less than other sources. The recent IPPC report[1] calls urgently for stronger measures to reduce transport emissions, stating that “Urban areas can significantly reduce emissions through transition of infrastructure, electrification, sustainable mobility and, e.g., pedestrian zones. Cities can achieve net-zero emissions, only if emissions are reduced inside & outside city through supply chains, that cascade across other sectors”.

- Reducing pollution. Pollution kills over seven million people each year[2] – especially the elderly, those with pre-existing health conditions, or even COVID-19 – and causes lung disorders such as asthma in children. It also costs our society 6.1% of global GDP[3].

- Reducing urban congestion. Urban motorised traffic congestion causes delivery companies to send out additional vehicles (which also sit in, and add to, the congestion) and makes journeys and deliveries less reliable. In Europe congestion costs 1% of GDP[4].

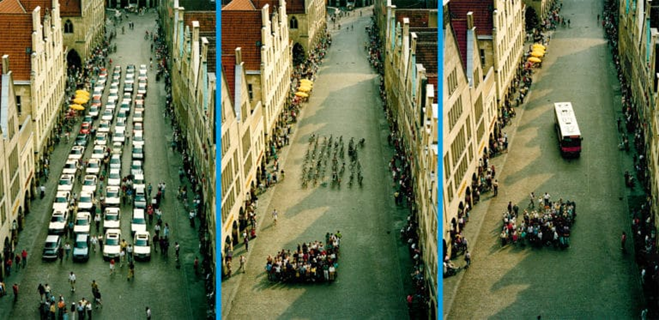

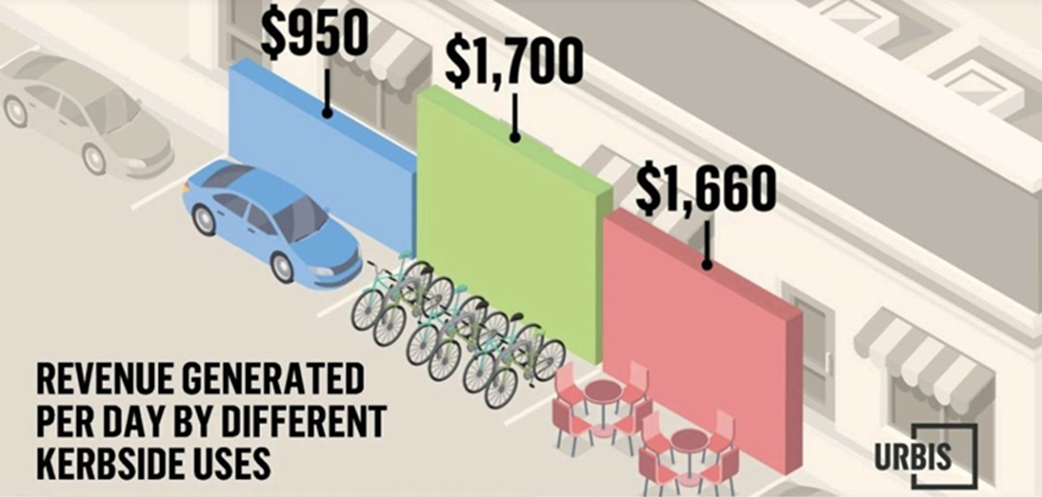

- Improving the urban quality of life. Converting road space for motor vehicles into recreational or commercial space results in a much-improved quality of life for residents. In the 1970s, the central squares of many European cities were filled with parked cars. Now much of that space is used for outdoor dining and recreation. The wide consensus is that areas so converted, with outside dining or shoppers as shown later in Ravensburg or Freiburg are far preferable to the town square filled with cars[5], and are more profitable for businesses[6].

- Safeguarding urban public space as a valuable resource. Space is limited in urban areas, particularly in cities, and due to this, the cost per square meter is usually high. At the same time, much space has been given free of cost (or for low cost) for parked and moving personal vehicles. This problem is worsening in many cities with an increase in the number and size of vehicles at the same time as an increase demand for housing in urban areas.

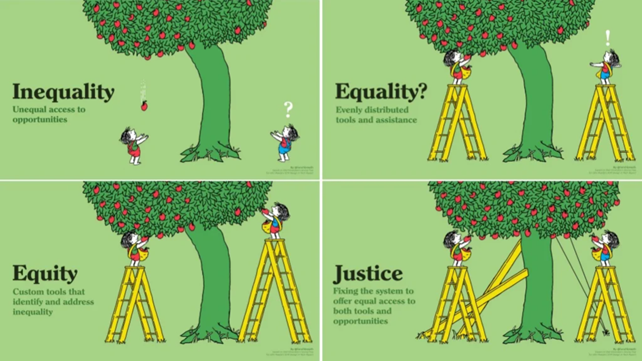

- Improve fairness and equity. People cycling, walking or using public transport travel more sustainably and consume much less urban space. Those who own no car (whether by choice or because they cannot afford one) are effectively subsidising the road space consumption and other costs caused by car drivers. (This issue is discussed in more detail in section 7.)

- Because sometimes “carrots” simply aren’t enough to achieve a city’s goals and the “stick” of an UVAR can be an effective tool to change behaviour. Even if there are good and affordable options available, many people still choose their individual motor vehicle – UVARs can help give a further ‘nudge’ in the more sustainable direction and make driving less convenient or possible than the sustainable option. Cities cannot always afford to make public transport as cheap as each as the cost of petrol for the same trip – the cost of the vehicle is often not considered by the user – UVARs can help alter the price.

Most people and companies change their behaviour when the alternative is

- more convenient or attractive,

- clearly cheaper, or

- their current option is not possible or is banned

UVARs can work as one half of an effective pairing of carrots and stick. When the UVAR ‘stick’ is combined with the ‘carrots’ of increased public transport, more attractive active mobility and sustainable logistics options, cities have the package they need to invite sustainable behaviour among their citizens.

The need to reduce climate emissions to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement is an increasing driver of UVARs, especially for traffic reducing measures and zero emission zones. While national policies can often improve the general conditions for lower emitting vehicles or fewer individual vehicles through taxes and other incentives, UVARs can help facilitate faster change in urban areas, where sustainable transport and the electrification of vehicles is easier due to generally shorter more predictable journeys and denser networks,

The European Commission outlines UVARs as a way to support many of these goals, in the paper “Reclaiming city streets for people: Chaos or quality of life?[7]”, and they support the aims of the European Green Deal[8] and the Urban Mobility Framework[9].

There are ever increasing numbers of regulatory UVARs being implemented in Europe. Over 800 schemes, including around:

- 440 low emission zones (LEZs),

- 450 pollution emergency schemes,

- 18 congestion charge schemes,

- 500 limited traffic zones,

- and increasing numbers of confirmed and planned ZEZs[10].

In addition, most cities, towns and villages have a pedestrian zone, and very many have parking regulations and at least some spatial interventions (road layouts that reduce traffic, speed or parking places). There are also increasing numbers of combined schemes, for example, congestion charging with differential charges for emissions, or traffic limited zones with emissions aspects required for the permits, to enable more flexibility and targeted action where needed.

[1] https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease/

[2] WHO, https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution

[3] World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pollution#1

[4] EC, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_559

[5] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352146517309158

[6] https://cleancitiescampaign.org/2021/12/09/why-fewer-polluting-cars-in-cities-are-good-news-for-local-shops-briefing

[7] https://environment.ec.europa.eu/all-publications_en

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

[9] https://transport.ec.europa.eu/news/efficient-and-green-mobility-2021-12-14_en

[10] Source: www.urbanaccessregulations.eu

1.4. About this document

This document is part of the ReVeAL toolkit, which consists of:

- This guidance

- The ReVeAL online UVAR decision support tool (see: AccessRegulationsForYourCity.eu)

- Detailed explanations of the 33 ReVeAL UVAR building blocks (see section 1) and the ReVeAL UVAR building block fact sheets

The different parts of the ReVeAL toolkit are detailed in section 2. The ReVeAL tools offer ideas on the kind of UVAR that might be relevant for a city, and indications of what needs to be considered when thinking about implementing an UVAR. There’s no single “recipe” or one-size-fits-all solution, but aspects that are often worth considering. The decisions often need to be taken using judgement while balancing different factors. The guidance is not intended to tell cities which options to use, but rather to help identify the questions to be asked and the factors to be considered in the decision-making process, so they can make the best decisions for their local context.

This purposes of the UVAR guidance are:

- To serve as part of the guidance provided by the ReVeAL UVAR decision support tool, AccessRegulationsForYourCity.eu,

- To provide guidance on the process of implementing an UVAR

- To address aspects that are common to all (or at least many) UVARs

- To focus on UVAR-specific aspects (as opposed to broader aspects of sustainable urban mobility) and

- To link out to other valuable resources where they exist.

We work in particular with the following existing documents:

- SUMP Concept

- SUMP Process

- SUMP Guidance UVAR Annex

- SUMP Guidelines themselves, as many of the ways of thinking about the UVAR process development are the same as those described in the SUMP Guidelines.

- C40 LEZ Guidance

- The-7-steps-to-create-effective-low-emission-zones.pdf (cleancitiescampaign.org)

- The Dutch ZEZ Guidance, translated into English here.

This document first explains the ReVeAL project, then looks at the process of UVAR development and finally looks in more detail at the different aspects of designing a good practice UVAR.

2. ReVeAL explained

An UVAR can be a simple or a complex measure. In the ReVeAL project, we break each UVAR down into its component building blocks, to allow an UVAR to be developed that suits your city.

2.1. ReVeAL building blocks and cross-cutting themes

ReVeAL building blocks

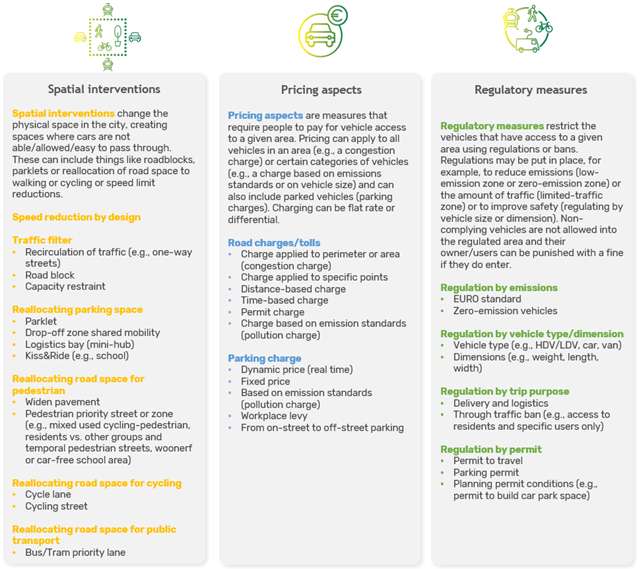

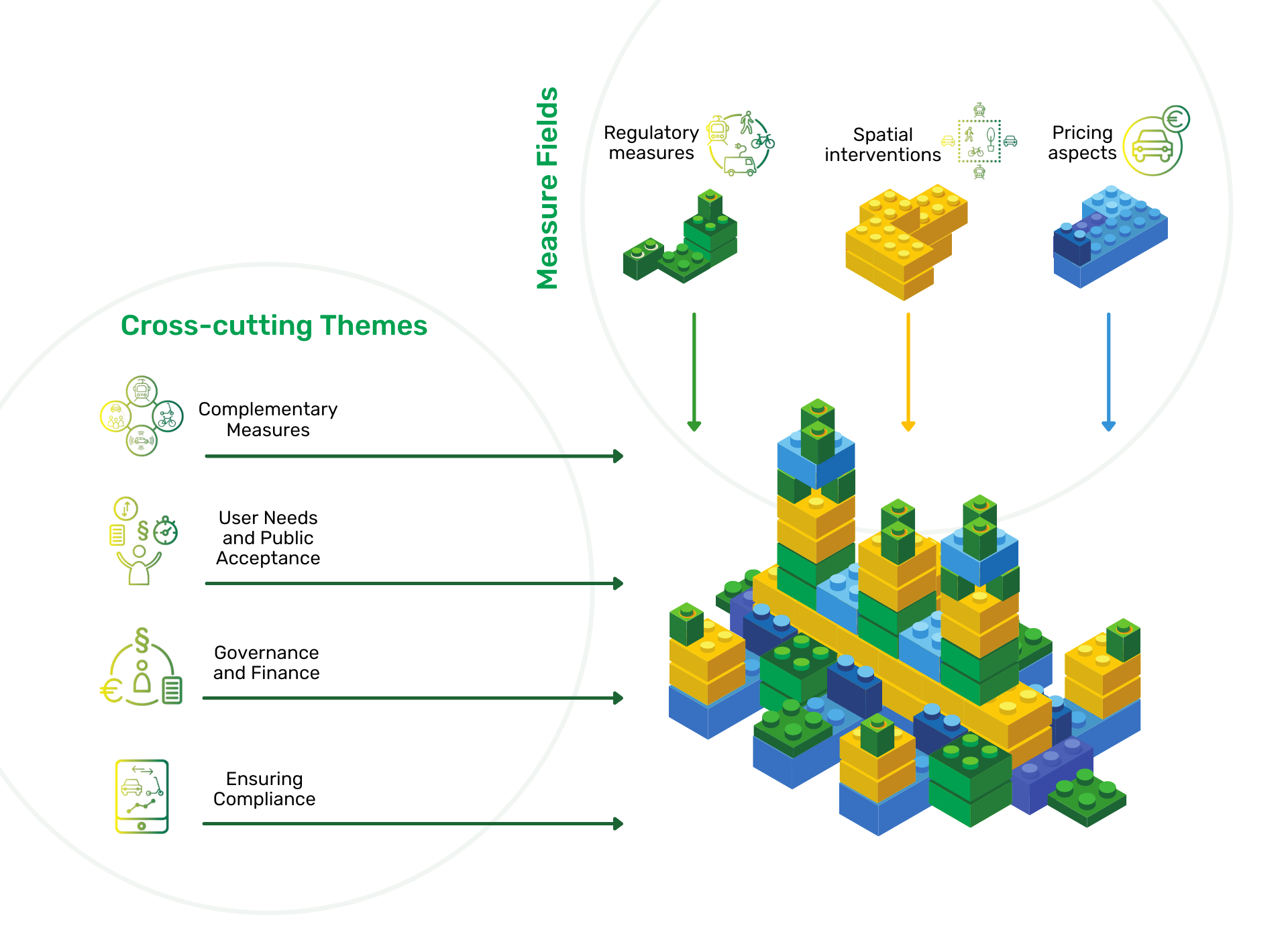

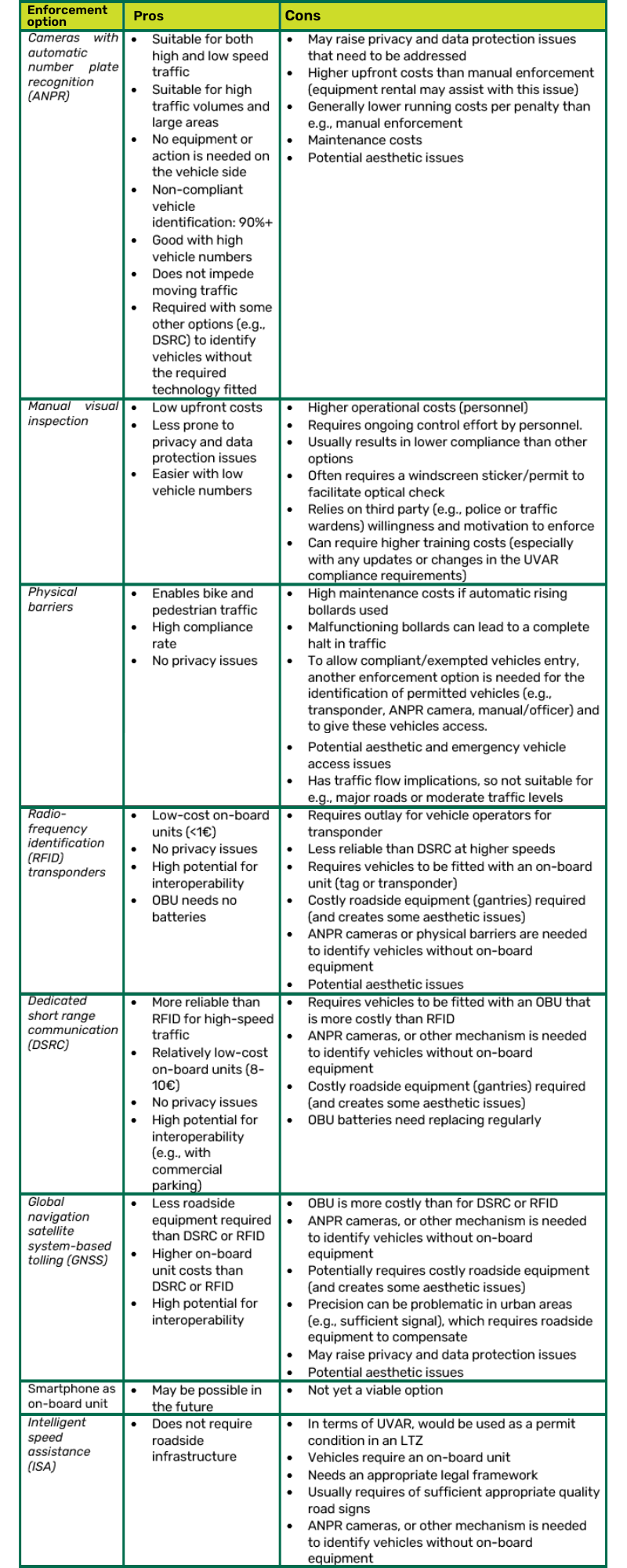

In order to understand what a complete UVAR “package” consists of, the ReVeAL project analysed a wide range of UVAR schemes to identify the constituent components of the scheme. 33 UVAR “building blocks” were identified that can be combined to create an UVAR package. The building blocks were categorised into three measure fields: 1) spatial interventions, 2) pricing aspects and 3) regulatory measures, and below that into 12 sub-categories. Building blocks can be combined within or across the three measure fields to create an UVAR package. See Figure 2 for an overview of the ReVeAL building blocks.

For each of the 33 identified building blocks in Figure 2, ReVeAL developed building block fact sheets. Each fact sheet provides a definition, a description of its implementation, which building blocks work well with each other, a case example of its use and other useful information about it. We discuss how to select the appropriate building blocks to create your UVAR in section 3.4.

Figure 2: UVAR building blocks and their categories, as defined in ReVeAL

Cross-cutting themes

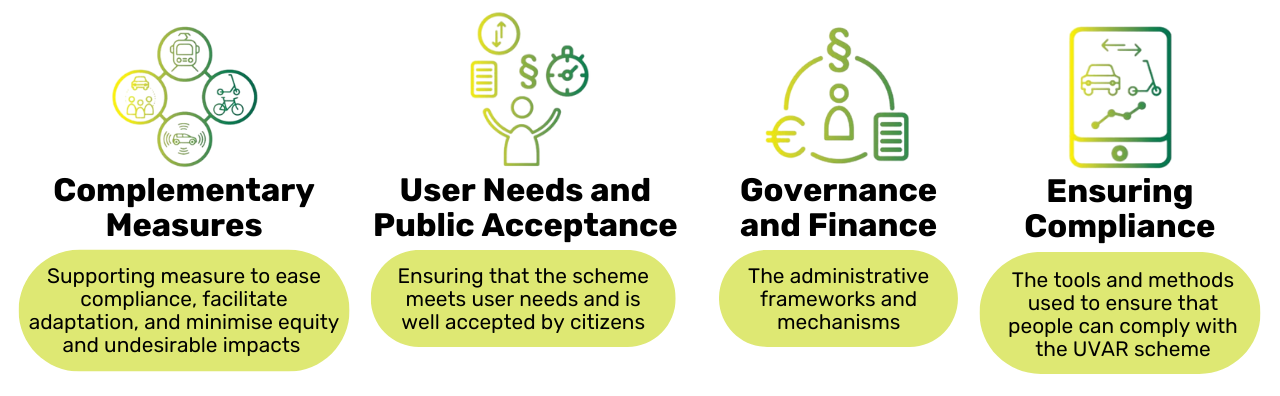

ReVeAL has identified four cross-cutting themes – that are relevant to all UVARs (see Figure 3). The cross-cutting themes user needs and public acceptance, governance and finance and ensuring compliance are described in detail in section 4, while complementary measures are discussed in this section. Complementary measures are cross-cutting in the sense that all UVARs need them, but the measures themselves are discrete measures that need to be combined with an UVAR, once a draft scheme has been developed.

Figure 3: ReVeAL’s four cross-cutting themes

The relationship between building blocks and cross-cutting themes can be visualised in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: How the components of ReVeAL fit together

2.2. Complementary measures

A supportive complementary measure is an additional measure that complements a planned UVAR to ensure access of people, goods or services into the UVAR area while maintaining the goals of the UVAR, easing compliance and facilitating the best adaptation to the new reality. It can also serve to minimise any equity issues that may result from the measure it complements.

Complementary measures can be crucial to making an UVAR feasible and successful. The planned UVAR should be implemented with an integrated package of supportive complementary measures to improve cost effectiveness and the performance of the UVAR with respect to the declared goal and specific objectives. Complementary measures can, for example, enable trips to be taken by transport modes not affected by the UVAR, facilitate a higher level of compliance or help to avoid a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged groups.

Complementary measures can also increase public acceptance by showing citizens that the UVAR is not just about requiring a change in mobility, but that it is implemented as part of a full package that provides concrete solutions to those who are asked to change their behaviour.

ReVeAL has identified four categories of complementary measures. These are:

- Complementary sustainable mobility measures

- Examples include additional public transport, increased or improved walking or cycling facilities, a consolidation centre, cycle logistics, micro-mobility, mobility hubs for different forms of shared mobility, a shuttle bus for those with reduced mobility or additional parking outside the zone[12]

- Financial or in-kind incentives

- Examples include grants for retrofits or exchanging parking/access permits for sustainable mobility vouchers

- Exemptions

- Examples include vehicles for people with disabilities, emergency vehicles, and – especially during the introductory phase – residents. For further details on exemptions, see section 3.

- Organisational support or other solutions based on the local situation

- Examples include pilot projects to support adaptation to the UVAR, linking service providers to one another, adapting the UVAR operating times or organising joint procurement[13] .

Supportive complementary measures can be added to and selected with the UVAR building blocks and can work as paired carrot and stick measures to encourage more people towards the desired mobility behaviour. The UVAR is the stick while the supportive complementary measures are the corresponding carrot. The overall scheme should include a balance of rules and restrictions together with services and opportunities that accompany them. The main thing to keep in mind is that the accessibility of people and goods is enabled, even if it is not with individual vehicles.

[12] There are SUMP topic guides on the implementation of many sustainable mobility measures. Sustainable urban logistics planning, micromobility, active mobility and electrification may be particularly relevant; all have SUMP topic guides. See www.eltis.org/mobility-plans/topic-guides. For logistics measures, there are the Sustainable Urban Logistics Plans (SULP) Guidelines. Additional guidance on parking can be found at Park4SUMP.

[13] examples of complementary measures, including organisational support are given in the Dutch Zero-Emission Zone Support Framework, also translated into English https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rp-fNiBilxPcDf9d-vaIXxcAUqqZhRGH?usp=sharing

2.2.1. Complementary sustainable mobility measures

Complementary sustainable mobility measures refer to the mobility schemes and related services that may be needed to help an UVAR to reach its full potential. Such measures aim to introduce, accelerate or maximise significant changes in mobility patterns or mitigate possible negative impacts of an UVAR implementation. They should make up a coherent package of accompanying or interlinked measures that support the restrictive nature of a specific UVAR scheme by making access to the area by other means easy and attractive. Such mobility measures can be classified into the following categories:

- Improvements in public transport

- Enhancement of cycling and walking

- Changes in parking system

- Enhancement of shared mobility

- Improvements in urban logistics

- Zero and low emission vehicles

- Ticketing and digital support

Ideally, complementary sustainable mobility measures are put in place at the same time as, or before, the UVAR scheme goes into operation. In addition, you may find after the implementation that some groups of citizens are unintentionally disproportionately affected by the UVAR scheme. In such cases, additional mitigating measures may be needed to compensate for this.

Context is essential when selecting complementary sustainable mobility measures to accompany your UVAR. Even before you have selected a particular UVAR, you should consider things that might affect the additional sustainable mobility services including:

- Main characteristics of the area in question: historic, touristic, industrial, financial, mainly residential, etc.

- The role of the city in the region (e.g., core city of a functional urban area, “feeder” town in a functional urban area, a city without an agglomeration, an independent town)

- Whether there are lots of visitors entering the city, and whether these are regular or occasional visitors

- Urban and demographic structure

- Environmental, economic and social variables (air quality, fleet composition, road safety impacts, population age, etc.)

- Current modal split

- Parking available outside the zone

It is important to keep in mind that the introduction of a UVAR will also impact those who live outside the city but visit it regularly for key activities such as work, health or education.

Example: Area C, Milan

In 2012, Milan introduced the congestion charge scheme, Area C, replacing its previous “Ecopass” pollution charge. The congestion charge is a €5 fee for vehicles entering Milan’s city centre between 7:30 and 19:30 (Monday to Friday) and is applied to an 8.2 km² area.

The scheme introduced a number of complementary measures. These included pricing integration of the access fee and the on-street parking fee for service vehicles[14] (e.g., maintenance or construction), urban consolidation centres for the reorganisation of last-mile delivery, a supply of reserved bays for the loading and unloading of goods and 20-minute free parking on paid parking spaces for loading and unloading[15].

Improved public transport was introduced at the start of the congestion charging scheme, with an increase in capacity of 75,000 passengers daily thanks to better services in metros, buses, and trams. Two more trains were added to the M1 line and one more train to the M3 (5% more capacity), frequencies on bus lines travelling to the city centre were increased and the peak-hour frequency was extended until 10:00. More staff was also temporarily employed to assist passengers.

Thanks to the Area C, and partly using its revenues, in 2013 over €13 million were allocated to the further development of metro lines, trams and buses and for the implementation of the second phase of the Milanese bike share system. At the same time, the municipality also financed a P&R facility, new 30 km/h zones and an upgraded cycle network to help promote sustainable mobility.

Any income gained from Area C is ringfenced for sustainable mobility measures.

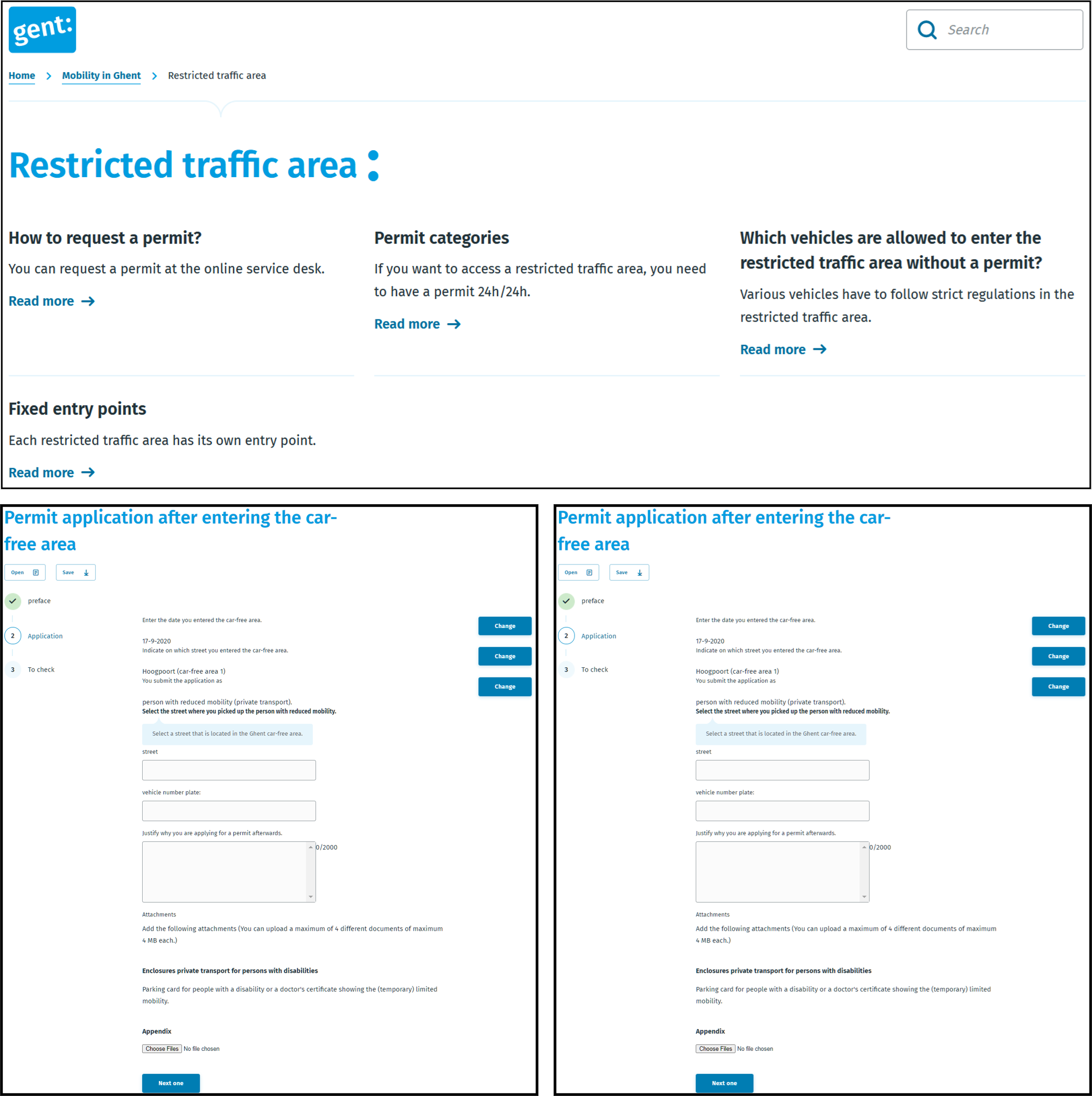

Example: circulation plan, Ghent

The circulation plan of Ghent is part of a larger mobility plan devised in 2012 in response to the rising amount of car traffic inside the inner-city ring. To prevent people from (needlessly) driving through the city centre, the circulation plan divided the central area into six separate zones (separated from one another by traffic filters) plus a car-free zone in the city core that is regulated as a limited traffic zone (with no on-street parking).

The City of Ghent also provides a free shuttle service between the city centre and two Park and Ride facilities on the outskirts of the city. The nine-seat minibuses connect to the city centre in less than 15 minutes. The frequency is between 10 and 30 minutes and the minibuses are active Monday to Saturday between 7:00 and 22:00 (midnight on Friday and Saturday) plus on shopping Sundays.

Other complementary measures include on-street parking immediately outside the car-free area exclusively reserved for residents (resident parking zones), cycle streets where cars may not overtake bicycles and about 7,000 bicycles available for rent at several bicycle points (some also served by the shuttle bus).

[14] https://www.comune.milano.it/servizi/pass-per-la-sosta-gratuita-non-residenziale

[15] https://www.comune.milano.it/servizi/area-per-carico-e-scarico-merci

2.2.2. Financial or in-kind incentives

Financial incentives are intended to make compliance easier, facilitate the most beneficial compliance method and address possible inequities. Incentives can be either cash or, preferably, vouchers for sustainable mobility provision. Examples include:

- Financial subsidies for fleet renewal (e.g., purchase, rental or leasing of greener vehicles, including tax exemptions or grants),

- Membership or vouchers for sustainable mobility options (e.g., discount cards, free rides or annual passes for public transport, shared mobility or consolidation centres)

- Monetary incentives for cycling (e.g., incentives for cycling to work or for the purchase of an (e-)cycle or (e)-cargo bike),

- Grants towards retrofits (e.g., diesel particulate filters[16], a new engine or fuel conversion) or

- Compensation (either financial or through a voucher) for the scrappage of an old vehicle – often differentiated by emission standards, vehicle type or owner income.

Many national, regional and local authorities have grant programmes to help fund the purchase or lease of electric vehicles, or the retrofitting of diesel particulate filters which can serve as complementary measures to the city’s UVAR. Private companies, such as car dealers or micromobility operators, sometimes use the UVAR to trigger their own incentives, for example targeting new fleets with specific marketing and prices for UVAR-compatible vehicles.

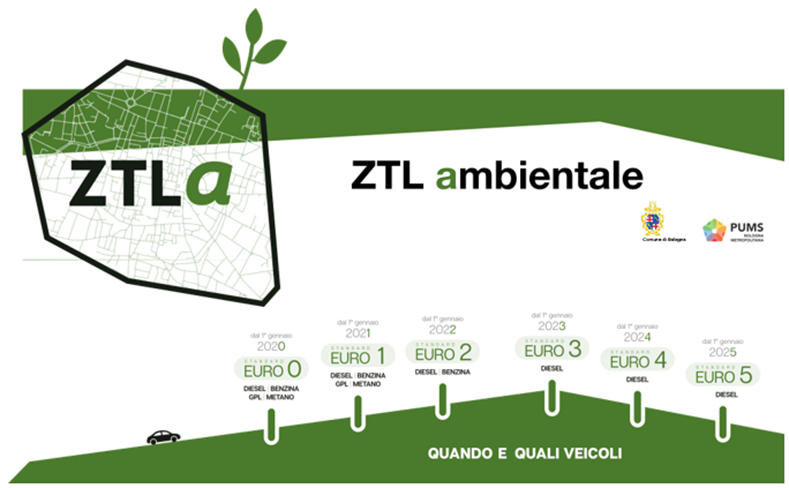

Example: mobility vouchers to mitigate adverse effects in Bologna

To accompany and support the addition of an LEZ to its existing LTZ, the municipality of Bologna introduced a tailored mobility bonus. Residents who opt for public transport, taxi, ride hailing, car sharing and bike sharing and who turn in an LTZ access permit, will receive a yearly financial voucher of:

- €1,000 per family if they turn in 2 permits associated to EURO 0 vehicles

- €700 per family if they turn in a sole permit associated to a EURO 0 (not if a Blue Badge)

- €500 per family if they turn in 1 permit associated to a EURO 0

The voucher can only be used for other sustainable mobility options. Via a dedicated website, residents can choose which amount of the voucher they want to use on which mobility option(s). The maximum duration is two years. Residents over age 70 can choose between the voucher and a 10-year free pass for the urban public transport network.

Bologna has also launched a funding scheme addressed to all residents and local companies who decide to buy a new e-bike (€500) or cargo bike (€1000), covering up to 50% of the total purchase cost.

Example: London’s guidance documents

Many supportive mobility measures are focused on awareness raising, guidance and improving alternatives to the private car to encourage the phasing out of the most polluting vehicles. Measures include improvements to public transport and walking and cycling networks and the ultra-low emission zone scrappage scheme, which allowed those on low incomes to scrap their vehicle for a one-off payment. Drivers also had the option to access a range of special discounts and deals such as a year’s free membership for the city’s popular Santander bike hire scheme. Another example is the City of London’s guidance for managing deliveries and servicing.

[16] This can also have the advantage of reducing emissions more significantly than a later Euro standard.

2.2.3. Exemptions

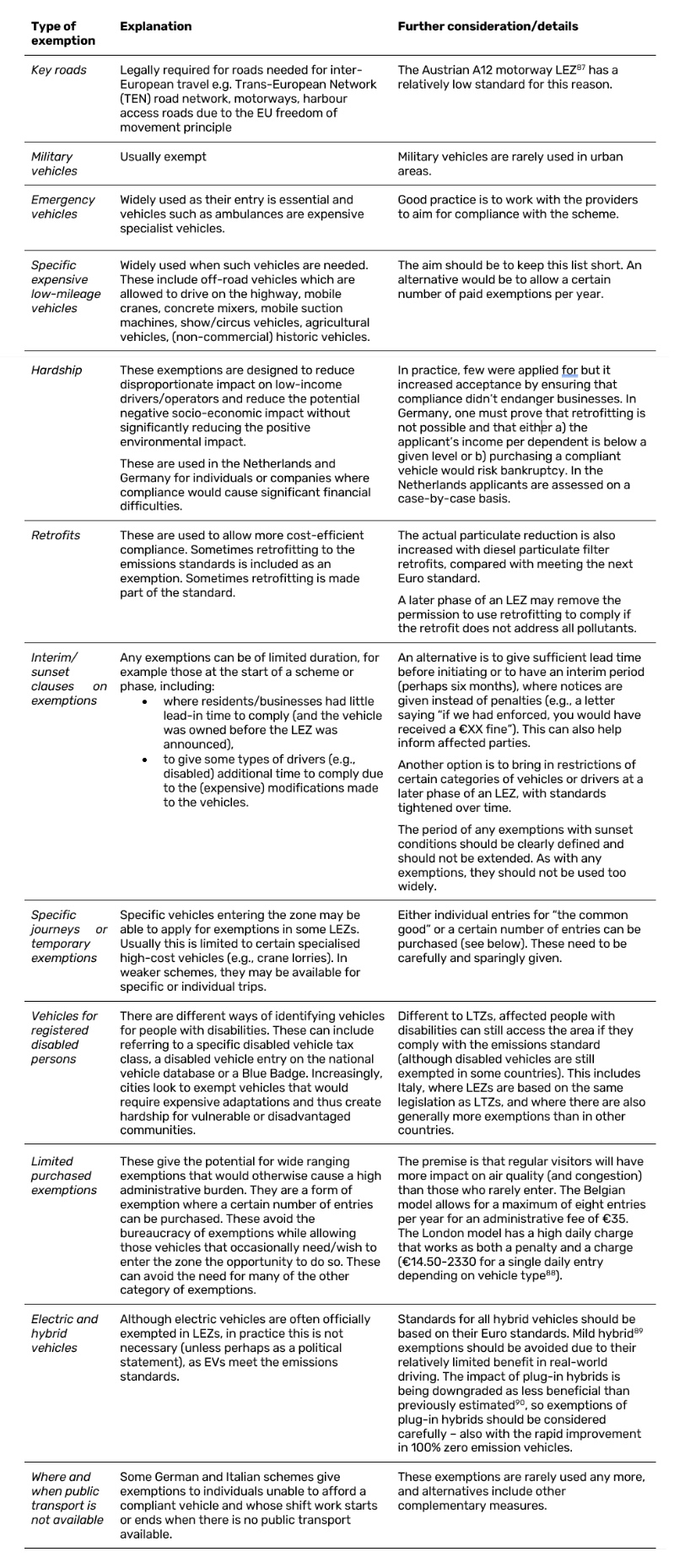

Exemptions can be used to make compliance easier and, when used carefully, they can help mitigate the impact on certain disadvantaged groups (e.g., people with a disability) or for emergency vehicles. Exemptions should be as few as possible and clear and transparent. Introductory time-limited ‘sunset’ exemptions can be useful.

Examples include:

- key exemptions (e.g., police, fire department, waste collection, etc.)

- user needs exemptions (e.g., taxis, residents, deliveries, people with a disability with forced car dependence)

- exemptions for adapted vehicles (e.g., retrofitted, converted or re-engined electric or hybrid vehicles)

- a limited numbers of purchased exemptions (e.g., a given number of entries per day/month/year, access to a specific zone, a quota of allowed kilometres to drive in the zone or “credits” allocated to individuals or businesses)

The types of exemptions will be different depending on the scheme type. For more details on exemptions see section 5.3.

2.2.4. Organisational support or other solutions based on the local situation

Such specific complementary measures can be logistical, administrative, promotional or other types of support that the city is in a position to provide. They might include supporting an alternative business model, for example, for a car park that will have no / fewer customers because of the city’s choice of UVAR measure. A city could also undertake projects to support the changeover to sustainable mobility, such as free trials of cargo bikes or shared electric vans, promoting a new e-scooter operation, or individual solutions to resolve specific local issues. It might also include promotional activities to encourage the take-up of people-friendly mobility option, or to make people aware of the problem the UVAR is addressing (see the example of Jerusalem in see section 4.4.2). Support could also entail changing the operating hours of the UVAR to enable certain groups access by car. For example, London moved the end time of its congestion charge from 19:00 to 18:00 so as not to affect the evening entertainment sector. Examples of organisational support used as complementary measures in the run-up to the Dutch ZEZs can be found on their website[17].

[17] Or https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rp-fNiBilxPcDf9d-vaIXxcAUqqZhRGH?usp=sharing translated into English

3. Getting started with your UVAR

3.1. Assessing the current situation to identify the problem

The first action of any UVAR development is to assess the ‘business-as-usual’ situation (i.e., what will happen if we continue on the same path). This helps identify the problem, what needs changing and which vehicles will be affected. For example: is the problem caused by commuters to the area or through traffic? Is it caused by light or heavy-duty vehicles? What sustainable mobility options are available for access to the potential UVAR area(s)?

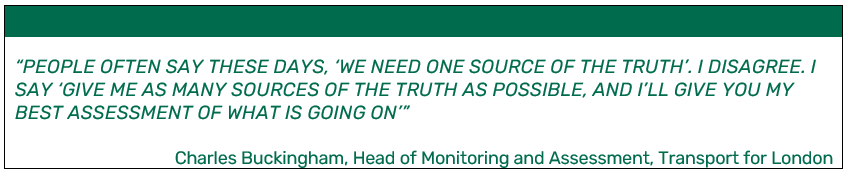

Many different sources and expertise on assessment are available; if it is lacking in the authority, it should be acquired. The SUMP guidelines can give a good start, and you may find the ReVeAL process evaluation and impact assessment framework useful.[18]

The amount of assessment needed will vary; a large controversial scheme in a large city will need more extensive analysis than a small more consensual UVAR. Usually in these assessments existing data is assessed, including, but not limited to:

- Motorised traffic flows, speeds, congestion, origins, destinations (possibly including the amount of through traffic or the number of commuters)

- Data on sustainable mobility, including cyclists, pedestrians and sustainable logistics

- Traffic composition (including data from automatic number plate recognition or manual counts)

- Air quality, climate or noise emissions inventories to assess the most significant sources

- Road safety data

- Demography of the area and its surroundings

- Land use of the area and its surroundings

The collection and analysis of data at the level of the functional urban area (FUA)[19] can be relevant, as many towns and cities receive significant amounts of traffic from outside their jurisdiction, where there may be fewer sustainable transport options into the city.

Questions relevant to the assessment include:

- What kind of change is expected to be triggered by the UVAR?

- What types of vehicles or users will be affected by the UVAR (long/short distance commuters, students, access to residential or commercial areas, large or small deliveries, residential or commercial delivery, etc.)?

- Which mobility / accessibility (or other) issue(s) may arise from the implementation of the UVAR? What unintended impacts are possible?

- How can the desirable changes be facilitated?

- How can undesirable consequences be minimised, especially for those on low incomes, those coming from outside the city area and the FUA, people with disabilities or with health needs?

Travel from outside the city can make up a significant proportion of car trips, as sustainable mobility options are often less available.

[18] It can be downloaded from the ReVeAL website here: https://civitas-reveal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/D4.1_Evaluation-framework_191129.pdf

[19] A functional urban area consists of a city and its commuting zone. Functional urban areas therefore consist of a densely inhabited city and a less densely populated commuting zone whose labour market is highly integrated with the city (OECD, 2012). https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/Dynaxibility4CE/UVAR-Topic-Guide.pdf gives guidance on UVARs in the FUA context.

3.1.1. Assessing the impact of different options

Assessing the different scenarios can help in selecting between them. It is also needed as part of the consultation process. The most common way to do this is to model the situation both before and after the UVAR has been implemented, under the same conditions. The “before” situation can be validated by data; assumptions will be needed for the “after” situation, which should be based as much as possible on data. In early stages of choosing among different options, an indication of the scale of the impact may be useful (for example from +++ to — for different parameters or indicators.

Neighbouring areas or authorities may be concerned that the UVAR could negatively impact them, however the UVAR may also improve the situation in the areas around the UVAR. For example, the positive impact of any journey that changes to cycling or public transport or to a lower emission vehicle will also be felt in the surrounding area. Modelling and assessments help estimate the impact; these can either reassure stakeholders or highlight areas where complementary measures are needed to minimise negative impacts that the UVAR might cause.

Examples of pre-assessments include from the Dutch ZEZs[20], Oxford’s ZEZ[21], and London’s LEZ and ULEZ[22] might be useful as illustrations.

[20] https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1EvyCYqk723Q5nYi7JHhmzmAqEs30GmxR?usp=sharing

[21]https://www.oxford.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/4019/zero_emission_zone_feasibility_study_october_2017.pdf

[22] Assessments of the LEZ: https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports/low-emission-zone and ULEZ: https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports/ultra-low-emission-zone

3.2. Your goal

The second step in developing an UVAR is to clarify the goal(s) that you aim to achieve by implementing it. An UVAR may help with many aspects of the city’s strategies, and it is useful to clarify which main goals the UVAR should achieve. For example, reducing traffic volume will likely also improve air quality and reduce noise, climate emissions and congestion. It may also increase walking, cycling and public transport use, improve safety and enable more liveable space, all of which may be city goals.

There are several factors that might affect the goal of the UVAR, including:

- the main mobility-related problem in the city,

- how the scheme is perceived and communicated, and therefore accepted (see section 4),

- the national law under which the UVAR is implemented

- an UVAR often requires a clear legal justification in the form of an identified goal that can be measured as having been met. If this is not the case, the UVAR may be vulnerable to legal challenges

It is therefore wise to have one main goal for which the new UVAR is being implemented and acknowledge that it will support other aims as well.

3.3. UVAR development phases

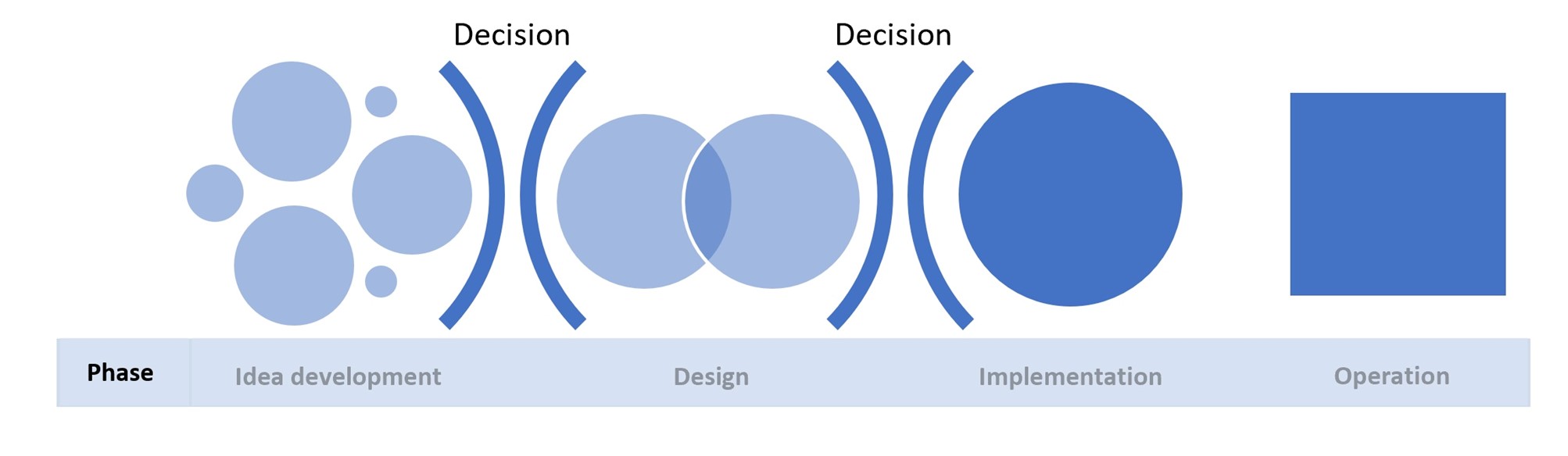

UVAR development can be seen in four phases, which are described below (see also Figure 5).

- Idea development

Here, the clarification of the goal the UVAR should be achieved. This stage should consider the type of UVAR, possible building blocks, an assessment of the existing situation and feasibility studies. The idea development phase ends when a political decision is made in principle to implement the scheme, a shortlist of options is created from a wider selection and a design, and any complementary measures, have been outlined.

- Design

Once the outline of the scheme has been created, the details need to be worked out. It may be that two options need to be assessed in more detail and a decision made between them. The designing of the required complementary measures would be included here. The design step ends with a political decision to implement a specific set of UVAR building blocks and complementary measures

- Implementation

The implementation phase prepares to put the plan into action. This will include making detailed plans, putting in place necessary legal changes, making the physical changes to the street, setting up any back-office systems, training staff, communicating the final scheme widely so that affected people can comply. If a pilot is considered, this could be implemented in this phase – or in the next phase if it requires more planning. The implementation phase ends the day the scheme starts.

- Operation

The operation phase includes enforcing and monitoring the scheme, as well as periodically reviewing it, to ensure that it is still fit for purpose. This phase ends only if the scheme is removed or there is a decision to update or change the scheme. An update or change would mean returning to step two.

Figure 5: Four steps in the UVAR development process

Figure 5: Four steps in the UVAR development process

The different phases described above can be useful to gain a clear picture of the process. At the idea development stage, many options are still open. In the design stage, the most promising ideas are developed further. In the implementation stage, a clear single UVAR “package” emerges, and the many details are worked out. In terms of what is done in each phase, there is no simple answer, as many of the activities in the UVAR development process are relevant in more than one – if not most – phases. And of course, an UVAR package is not developed and implemented in a vacuum. It needs to be incorporated and aligned with the many ongoing processes and existing plans in a city. That’s to say, the process is a fluid and iterative one, and decisions are often not clear cut.

Many of the issues detailed in this guidance arise in several different UVAR development phases. For example, assessment and monitoring are needed in idea development (to understand the problem and therefore what needs to be changed), in the design stage (to estimate the impact), in the implementation stage (to get a more detailed assessment of the impact of the chosen scheme) and during the operation stage (to assess success and identify if/when changes are needed).

3.4. Selecting building blocks

Developing an UVAR is best done using a participatory process. One way to approach the process is through a series of workshops with selected stakeholders to select the building blocks (and then complementary measures) that are most appropriate for the city’s UVAR.

Different stakeholders will need to be engaged in the process, both to ensure that all aspects are considered, as well as to gain buy-in for the scheme. Stakeholders range from colleagues from different departments in the city authority, politicians, different layers of government and many different aspects of society, (see further details in the Stakeholder involvement section 4.2). As with many things, a balance needs to be struck; you and your colleagues know your city, its stakeholders, and the context of the UVAR development best. Even if there is no or little history of participatory development in the authority, it is worthwhile trying it.

Involving stakeholders early in UVAR discussions will likely be better received than presenting them with a completed scheme; early involvement enables them to understand the purpose, offer constructive comments and help inform the development of the scheme, rather than being faced with a finished scheme to criticise. An UVAR development process that is and, importantly, is also seen as, transparent, open and fair can help increase public acceptance and ensure that legitimate (see section 4.3) are appropriately accommodated. Ensuring an inclusive UVAR development process helps achieve this.

Carefully considering the groups that you gather feedback from will ensure that your scheme is equitable and reflects the needs of the people who will be affected by it. This includes representatives of groups that may have particular needs, such as people with disabilities, the elderly or parents with children.

Workshop participants need to be informed about the process and the building blocks, as well as the current assessments that have been undertaken of the city/area, so they are in a position to make decisions. The REVEAL building block fact sheets clearly explain the building blocks and provide concrete examples to ease this process. Making the materials available in advance is useful to achieve this, as well as introducing them in the first workshop.

During the workshop, each participant ranks each building block in terms of how relevant they feel it is for the area under consideration for an UVAR. After this, a discussion among the participants of their choices, and the reasons for them, is useful. The different perspectives and opinions expressed may impact a participant’s initial choices and they may want to modify the rank given. Another round of workshop(s) might be done after making a shortlist of options, after combining different views and assessments, and / or with different workshop attendees.

The ReVeAL project also created an online decision support tool, which is intended to help users identify which UVAR building blocks might be appropriate for their local context. The online tool can help by steering the user to a combination of different UVAR building blocks that may become the basis of an UVAR package that suits the city. The ReVeAL decision support tool can be used to help participants identify the building blocks with the highest potential for success in their situation. One way to use the tool: in a first workshop, participants discuss building block options and comes to a general agreement on some that may be valuable. In a second workshop, the participants use the ReVeAL tool to see if it offers any new options. The differences and similarities can be compared and discussed.

Whatever format is used, the highest ranked building blocks would be selected, the aim being combined to create a coherent UVAR package. When deciding between different options, an estimate of the impacts of the options may be needed – with indicative impacts at early stages and later rounds of assessment being more detailed. The selection may need to be reviewed, and steps repeated depending on the combinations selected, or assessments undertaken.

Ideally, these processes will lead to two or more different “packages” of building blocks for the project area or different areas, where different building block combinations, geographic scales, timing or implementation conditions are considered. These scenarios can then be assessed in more detail during the design phase in order to choose between them.

3.5. Selecting complementary measures

A complementary measure is an additional measure that complements a planned UVAR to ensure access of people, goods or services into the UVAR area while maintaining the goals of the UVAR, easing compliance and facilitating the best adaptation to the new reality. It can also serve to minimise any equity issues that may result from the measure it complements. It is useful to keep these in mind even at early stages of UVAR development; as they may make a building block possible or acceptable that otherwise would not be. They can also facilitate a more sustainable adaptation to the UVAR, reduce any undesired negative impacts on certain sectors of society or enable essential transportation needs. The need for complementary measures may arise from the project inception, in assessments, stakeholder workshops or through an understanding of the cultural, social and political situation in the city.

The UVAR should ideally be integrated into the city’s SUMP, which helps combine the planned mobility measures to maximise the impact of an UVAR. When deciding which complementary measures will accompany the UVAR scheme, it is also useful to consider any relevant measures that are foreseen for the future to determine if these could be brought forward to support the UVAR.

Questions that were relevant during the assessment (see section 5.1.2) are likely to be relevant in considering which complementary measures are needed.

As with selecting building blocks, selecting complementary measures should be done in using participatory processes and consultation with different communities. When selecting a specific complementary measure (or a package of measures), it is important to consider:

- How will the complementary measures respond to the issue(s) arising from the implementation of the UVAR measure?

- Does the implementation of the planned complementary measure (or package of measures) address the actual user needs? (see user needs in section 3)

- Is the timing appropriate? (i.e., before the UVAR is implemented, or at the time it is implemented)

- Has the planned supporting measure been used in the past elsewhere in this or similar cities? Was it successful?

- Does the city have the competence and resources to implement the measure? If not, who else needs to be involved?

There will also be the question whether, and how, to accommodate which groups – as many of those affected may call for special treatment. Decisions on legitimate concerns vs. self-interested desire to avoid change need to be made based on evidence and moral, political and operational concerns informed through stakeholder engagement[23]. In the London congestion charge, no concession was made for the Smithfield meat market workers, for example. However, the end time for the daily charge was brought forward from 7 pm to 6 pm to avoid the evening shifts of theatre and restaurant staff and address wider concerns about the evening economy[24].

[23] The issue of who to give special treatment is also discussed in the stakeholder engagement section 4.2

[24] https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/How-road-pricing-is-transforming-London-and-what-your-city-can-learn

4. ReVeAL cross-cutting themes

As described in section 2.2, ReVeAL has identified four cross-cutting themes that are relevant to all UVARs (see Figures 2 and 3). The cross-cutting theme complementary measures is described above. The themes user needs and public acceptance, governance and finance and ensuring compliance are described in this section.

4.1. Governance

For ReVeAL, good governance implies transparent procedures for policy and project design, project management, procurement, financial management and allocation of revenues at the local level. In many cases, policy and operational coordination is needed between different levels of government affected by the UVAR.

At its best, effective governance translates into professional project management of the UVAR scheme, with accompanying measures (short and long term) institutionally anchored by means of a specific agency/authority, different agencies working together or through the establishment of public-private partnerships.

Key aspects include:

- Decision-making context

- Legal frameworks (national and local)

- UVAR-specific EU legal issues

- Institutional setting and organisational arrangements

- Policy frameworks and planning instruments

- Political instruments

- Enabling sufficient resources (human and financial)

- Integration and interaction of cross-cutting themes (including champions; see below)

- Communications

Each of these is discussed in more detail below.

4.1.1. The decision-making context

Understanding the decision-making context is a key step to understanding the governance opportunities and challenges behind an UVAR. When assessing this, some of the questions that need to be answered are:

- Who makes UVAR-related decisions? Identify the leading councils, elected leaders, civil servants, etc. in the UVAR process, at the local level as well as the regional and national levels.

- Who formulates technical solutions? Identify the leading technical employees within the city, including planners, engineers, transport designers, and the leading external or contracted technical experts in the UVAR project.

- What is the approval process and who is involved? This could be horizontal within the local government or vertical among the different levels of government.

- Which are the leading voices and organisations that affect the UVAR project (both supportive and opposing)? This could include civil society, citizen-led groups or residents, business associations, opposing political parties, etc.

- Is there a champion[25] leading the process from within the authority or pushing it from outside? This can significantly increase the success of the scheme, especially if it is a leading politician. When introducing a new policy to the public, this can be a critical factor in success.

- What is the estimated level of participation /opposition from the public and are they any particular groups that are particularly relevant? Such groups should be identified, and communication established.

- How is the UVAR process to be managed across different government departments within a municipality and regarding the interface with other government agencies? It is important to have one body that is clearly seen as the “lead” and communications core.

When implementing UVARs, it is important to have the electoral cycle in mind (including elections, the beginning of a campaign, decision-making standstills before and after elections, etc.) and how it could impact the UVARs. It helps to try to foresee if the UVAR will be implemented within the electoral period of those deciding the scheme. The greatest resistance to a scheme generally arises around the time of implementation (see the public acceptance section 4.3), so there is a significant advantage of the scheme being implemented at least a year before the end of the legislative period so that the changes can be accepted and the improvements acknowledged before the next election. If the scheme cannot be implemented within the electoral period, will the scheme have sufficient cross-party support to be implemented over more than one electoral period? Another (riskier) option is to complete detailed preparation in one electoral period and for the politicians to seek re-election on the basis of its implementation in the next period.

Different organisations can influence decisions related to the UVAR lifecycle. These include both public administrations (e.g., city council, regional government, national government), as well as expert commissions, political parties, interest groups or other stakeholders. The interests, concerns and needs of different groups must be considered from the early stages to make an UVAR a success. As discussed in the stakeholder involvement section (4.2), it is important for involvement to be with a full cross-section of society, including women, youth, the elderly and people with disabilities, who may otherwise be under-represented in discussions.

[25] Champions are people willing to invest their resources in return for future policies they favour. Their motivation may be a concern about certain problems, the promotion of policy values, professionalism, or simply the satisfaction of participating. Champions can be elected officials, civil servants, activists or journalists, groups or individuals. The presence of an appropriate and skilful champion can improve a measure’s chances of moving up on the agenda if this figure makes the critical ‘couplings’ when policy windows open, as well as being publicly acceptable by setting the tone of the discussion. A city staff member plus a politician or political group, can make a good champion team.

4.1.2. Legal frameworks

It is crucial to determine from an early stage whether national legal frameworks or guidance[26] exist for the implementation and efficient enforcement of the selected UVAR. Some of the possible issues include the right to ban certain vehicles from an area or charge them to be there, the use of automatic number-plate recognition for camera enforcement, sending fines, identifying complying vehicles or the use of transponders. The requirements for its financial management, personal data protection, tendering and procurement must also be established.

It is also important to know if new local regulations are needed to implement the UVAR, or whether new or altered national legislation is needed. Sometimes mechanisms can be (legally) used for purposes for which they were not designed; for example, the Italian limited traffic zone legislation allows cities to add conditions to gain access. This makes it possible to turn those LTZs into other schemes or combined schemes. For example, an LTZ can become:

- an LEZ, where the only access conditions is meeting the emissions standard

- a congestion charge, when entry is upon payment,

- a combined LTZ-LEZ, where vehicles are limited by the LEZ and those vehicles that are permitted must meet emissions standards

- a toll-LEZ as in Milan’s Area C[27].

Another example in London is the existing congestion charging legislation was also used to implement London’s LEZ and ULEZ, with high “charges” for non-compliant vehicles (which could also be seen as a fine and daily exemption permits).

There are often different ways to implement an UVAR (and complementary measures), so it is important to identify the most appropriate one for your local context. For example, Berlin’s low emission zone bans non-compliant vehicles – and then charge a fine for non-compliance. On the other hand, Oslo uses a road toll for its LEZ[28] that varies with emissions and removes road space for vehicles in its ZEZ[29]. A large car-free area with spatial interventions can be used instead to create a (nearly) zero emission zone if the legal framework for a zone that bans combustion engines is not available. It may then be possible to put conditions on, for example, delivery and other vehicles entering the area, requiring them to be zero emission.

It might be difficult to put a new UVAR in place within an existing legal framework, and creativity might be needed. Examples of non-standard processes include using existing legislation for a slightly different (but still allowed) purpose, the use of a trial or experimental traffic regulation orders or the use of voluntary compliance – or a combination of these. Within ReVeAL, both Bielefeld and the City of London used experimental traffic orders to test an UVAR in real life, before committing to it. It should be noted that further traffic order processes would be needed to continue the scheme beyond the experimental period, and the monitoring and assessment requirements of the different options can be different.

As a different approach, Jerusalem worked with local and national legislators to update the local and national legal frameworks to allow it to use camera enforcement for its LEZ. Changing the law is possible, but not easy and therefore not the first choice. All other avenues should be pursued before choosing the route of changing the legislation. Voluntary schemes should be used with caution, due to their low compliance rates.

When there is more than one scheme of a certain type in a country or region, there is significant advantage to having as much commonality as possible among them. This leads to greater acceptance and avoids the confusion and annoyance to drivers of slightly different schemes. Regional authorities in German and northern Italy harmonised their LEZs. In Germany, common emissions standards were set for all cities with an LEZ in their region. In northern Italy, there are LEZs in all cities with more than 30,000 inhabitants. This was done to ease communication and understanding, and to avoid concern from the retail sector that shoppers would go to the neighbouring (non-restricted) city.

Cities new to UVARs would be well advised to first identify whether there are models elsewhere that might be suitable for their city, and to work with the national level of government, and/or with neighbouring cities or countries to reduce the number of different schemes. New UVARs should be as similar as possible to existing schemes, differing only when needed. Road user or congestion charges usually need their own specific legislation. All schemes need appropriate legislation, but there can sometimes be flexibility on which legislation is used.

EU legal issues

The aspect of EU law that most affects UVARs is the EU Freedom of Movement Principle, one of the key aspects of the EU treaty. In terms of EU law, an UVAR is a potential barrier to trade, but depending on how it is implemented, it can be justified under Article 30 of the EC Treaty, which provides an exhaustive list of grounds for exemptions from the Freedom of Movement Principle, one of which is the “protection of the health and life of humans, animals and plants”.

The other two aspects of EU law that affect UVARs are the proportionality and non-discriminatory principles – so schemes must be proportional to the problem, and not discriminatory. This means in practice that:

- UVARs should not be any harder for foreign vehicles to comply with than for vehicles of the home country. Information on the UVAR should be spread EU-wide if foreign vehicles are affected (this is often necessary for public acceptance).

- The freedom of movement principle also means that the emissions or other standards and retrofit certification should be able to be met EU-wide. For LEZs this means that the standard should be in line with the EU vehicle Euro standards, age of first registration or for retrofitting UNECE REC[30] for heavy duty or construction vehicles or related to the Euro standards for light duty vehicles. This may also have implications, for example, for C-ITS options such as ISA (see section 4.1), which need to be carefully considered.

- Motorways and the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)[31] key roads need to be exempted from LEZs and other UVARs, or have an appropriate diversionary route (which in practice is difficult for motorways).

- Most of the time “non-discriminatory” is interpreted at national level as within the scope of application of the Treaty that established the European Community and the Treaty on European Union, and under which any discrimination on grounds of nationality is prohibited. This right is enshrined in article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights. This includes any discrimination based on sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation. Thus, attention is needed to ensure that there are no unforeseen exclusions due to income, gender, age or ability with the introduction of an UVAR.

[26] For example, the Dutch logistic ZEZ Roadmap

[27] See further information in section 2.3 or https://urbanaccessregulations.eu/countries-mainmenu-147/italy-mainmenu-81/milan-area-c-charging-scheme

[28] https://urbanaccessregulations.eu/countries-mainmenu-147/norway-mainmenu-197/oslo-charging-scheme

[29] https://urbanaccessregulations.eu/countries-mainmenu-147/norway-mainmenu-197/oslo-zero-emission-zone

[30] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/uniform-rules-concerning-the-approval-of-retrofit-emission-control-devices-rec.html , https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/main/wp29/wp29regs/2015/R132e.pdf, https://wiki.unece.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=2523175

[31] https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-themes/infrastructure-and-investment/trans-european-transport-network-ten-t_en

4.1.3. Institutional setting and organisational arrangements

When assessing the context, and in the initial idea development and design phases, a city must ensure that it has competence, not only for planning and deploying the selected UVAR, but also for operating and enforcing it. If the city does not have full competence for any of these aspects, it should identify what other institutional actors need to be involved (e.g., national government, national police, regional government, etc.). Some aspects of the UVAR might be outsourced, and these should be identified.

Different political processes and events may have an important impact on the UVAR process (e.g., local elections, political party agreements). At the same time, there are a variety of political instruments which can be used in different moments of the UVAR lifetime to support the UVAR process (e.g., consultation and participation processes). Periodic monitoring reports are key for the necessary assessment of, and support for, UVAR measures and confirming support for their implementation (or changing them if needed to gain support). These are also key to successful communication with the general public. Aspects related to equity, equality and fairness should be considered within the monitoring process of the UVAR.

It is worth cooperating with other cities and stakeholders for the resource-efficient implementation of easy-to-communicate UVARs.

4.1.4. Policy frameworks and planning instruments

It is helpful to identify policies that will be relevant to the planned UVAR. These can address topics such as air quality, congestion, accessibility and climate, but also land use, public transport, parking, cycling, innovation, equality, equity or economics amongst others. Many cities have policies covering these areas. It is important to ensure that the objectives of the UVAR align with the city’s existing policy objectives, and that there is a process to align the implementation of the UVAR with these policies.

Especially for a high-impact or controversial UVAR, it helps to work within the framework of an integrated, long-term plan, such as a SUMP. The integration of the UVAR in a SUMP ensures that the UVAR is integrated in, and supported by, a comprehensive mobility strategy. It can offer a structure of existing stakeholder groups or communication processes which can support the UVAR implementation process, and also address sustainable modes of accessing the areas concerned that may benefit specific communities. The SUMP Topic Guides, including one on UVARs in SUMP, might be useful here.

Different UVARs and different situations in the city might call for different approaches with respect to SUMPs. For example, neighbourhood level UVAR schemes may not be appropriate to reference in the city’s SUMP, but they should fit in with the SUMP aims. An urgent problem may need to be addressed outside the SUMP framework, but again, ideally aligned to the SUMP aims.

A SUMP might need an update – for example to enable a new mayor to implement an UVAR within the first half of their electoral period so benefits are seen before the next election (see the public acceptance section 4.3 and governance section 4.1). An UVAR may be a key or supporting component when a city develops its first SUMP, and it should certainly be considered by any city undertaking a SUMP. Ideally, the planning of an UVAR measure is undertaken together with urban planning process right from the beginning – but in reality, this is not always be possible.

An example of good practice in the integration of UVAR and SUMPs is provided by the Spanish ReVeAL city of Vitoria-Gasteiz. The superblock scheme[32] was used in their SUMP[33] as the main tool to achieve the objectives of the city.

The Belgian city of Ghent’s circulation plan is another good example: the circulation plan was developed as a chapter of the mobility plan to highlight it as an integrated measure that was part of the overall strategic vision of the city.[34]

[32]https://www.interregeurope.eu/sites/default/files/inline/14._Superblocks_streets_designed_for_sustainable_mobility_in_Vitoria-Gasteiz.pdf

[33] Superblocks in Vitoria Gasteiz’s SUMP https://civitas-reveal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Incorporating-UVARs-into-the-Vitoria-Gasteiz-SUMP-red.pdf

[34] For further information on the Ghent Circulation Plan you can visit ReVeAL’s webinar ReVeALing Space for People: Ghent’s UVAR ReVeALed.

4.2. Stakeholder involvement

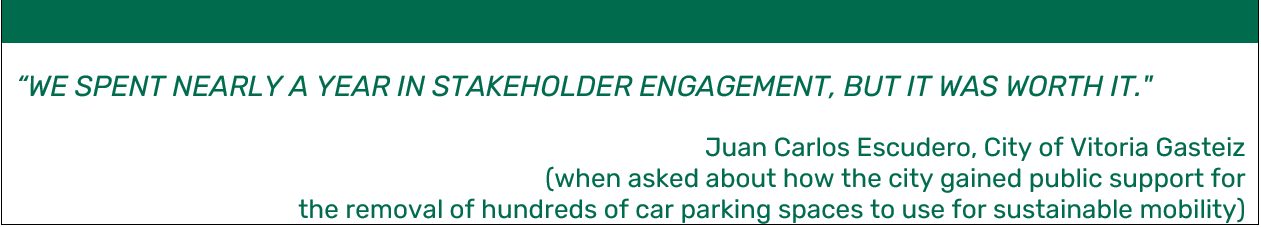

As with the SUMP process, stakeholder involvement is an essential part of implementing an UVAR. This is because it is likely to make a better, more accepted and adapted scheme. Taking the extra time and resources to engage with different users can seem to make the planning process expensive and risks making the outputs inconclusive. However, these efforts can uncover issues not previously considered by experts. They can also be a source of innovative solutions.

Stakeholder involvement needs to be designed so that it hears more than the voices of those resisting any change that will inconvenience them. A judgement will need to be taken as to which concerns are legitimate, and which simply want to resist change. Care needs to be taken to ensure that voices such as those of youth, women, minorities and those with disabilities are heard as clearly as those who may otherwise have undue influence over the process.

The city of Bielefeld, Germany, was very open about what could be done in its Old Town and had good (and plentiful) experience with stakeholder involvement. They developed an interactive website to gather input on their planned UVAR measures, held online meetings during the pandemic and maintained working groups to ensure the scheme could be discussed and suggestions included.

4.2.1. Stakeholder engagement strategy

A stakeholder engagement strategy should be developed at an early stage of your process to define how to engage with stakeholders during the UVAR development process. Aspects to include in your strategy are:

- Identifying and understanding your stakeholders

- Forms and methods of engagement to be used

- Level of engagement (inform, consult, collaborate or empower[35]) and decisions about which stakeholders to involve at which levels

- Timing of engagement activities (also what information to provide when)

- Required resources (skills, budget, time)

- Ensuring the voices of all socio-demographic user groups are reached through appropriate channels (e.g., the elderly, the youth, residents and commuters, etc)

[35] http://intosaijournal.org/inform-consult-involve-collaborate-empower/

4.2.2. Identifying and understanding your stakeholders

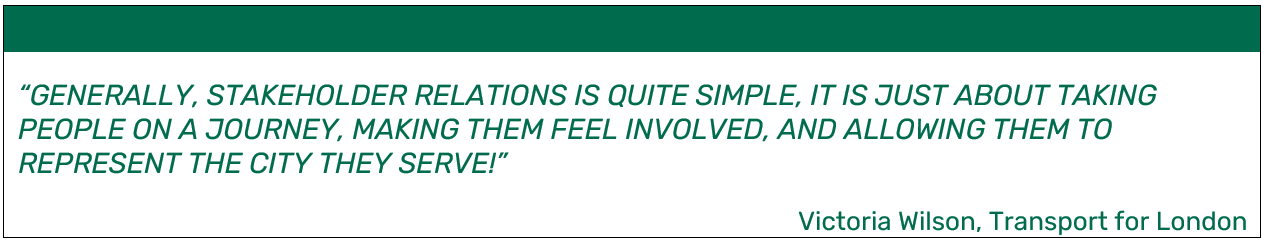

It is important to include stakeholders from both inside and outside the local authority, from both inside and outside of the UVAR area and from the city’s entire functional urban area (FUA)[36]; those who currently travel into or through the potential UVAR area will likely have different access needs from those who live within it[37]. Grouping stakeholders can help ensure that all are identified, but it is important to ensure that all voices are heard.

Generally, it is valuable to involve as many stakeholders as is relevant and practicable. Figure 1 gives an outline of possible stakeholder groups to identify. It may help to try to reach out to specific organisations that both bundle the concerns of a given group and have direct access to members of the group.

Table 1: Possible stakeholder groups to engage

It is also important to ensure that you reach different cultural and socio-economic groups among your stakeholders and that you achieve a gender balance so that as many voices as possible are heard (see also Equity section 4.7). In some cities there will also be different languages to consider. By doing this, you will hear the needs to be addressed in the planning and implementation from those who stand to be affected. It also enables people to be involved in the process; they may be less likely to oppose it afterwards if they have an understanding of the issues at stake. Thorough work here will help you avoid costly mistakes at a later stage if you inadvertently neglect important stakeholder groups.

Some people will stand to benefit from the proposed UVAR, while others will feel they are being (unjustly) “punished” by it. In some cases, the perceived punishment is rather the removal of a privilege (such as eliminating long-standing cost-free car parking). It may also mean that there will be an extra cost (in time or money) to those who are already disadvantaged but who have no choice but to rely on a car. UVARs need to account for the needs of people with mobility challenges to ensure that they are still able to access the city. The art is to decide whose needs or potential disadvantages may warrant an exemption or complementary measures. It is worth the effort to understand where stakeholders are coming from and what their agendas are – hidden or otherwise. For example:

- Whom do they represent?

- What are their objectives?

- What do they have to lose or gain?

- How much influence do they have?

It may require extra effort to gather input from those with much to lose, but who have (perceived or actual) little influence, or those who will benefit from the UVAR (and are therefore less likely to feel the need to express their views about the scheme). These groups are typically more difficult to engage with, but they are also those at greatest risk of being excluded by the implementation of the scheme if their needs are not understood.

Where relevant, providing information on your UVAR plans in relevant local languages may be helpful for building trust and understanding and gaining valuable input. Likewise, meeting people at a time and place that works well for them (as opposed to being most convenient for you) will also provide you with insights that you would not otherwise get. You also need to be sure that the voices of those with significant influence, but little to lose, do not drown out others.

It is useful to have a balance of those (likely to) support and to oppose the plans in the same room. It also helps to include some strong supporters and allies, so that you are not the only one talking about the benefits of the proposed scheme. A fluid and transparent conversation needs to be created where every group’s arguments, as well as real and perceived concerns are heard, considered and included. At the same time, the goals and opportunities of the UVAR(s) upon which the authority will not compromise need to be transparently presented. Complementary measures, such as case-by-case exemptions or the ability to buy a limited number of day passes, can prevent marginalised groups from being disproportionally impacted.

It is important to clearly set the limits of influence of stakeholders so as not to raise false expectations. Where and when decisions are expected from them, and there should be sufficient information on which to make informed decisions. The REVEAL building blocks and fact sheets can be a helpful resource to inform stakeholders.

People and goods will need to move around and into the area, meaning it is important a) to get buy-in from those living and working there and b) that they can still access the UVAR area. Neighbouring authorities may fear the UVAR will shift traffic and worsen the situation in their jurisdictions, whereas in fact, it is more likely to improve their situation. This is because people who change mode may well switch farther away, meaning they are on a bicycle or bus through the areas neighbouring the UVAR. And a low emission zone leads to more low emission vehicles in all parts of the city and its surroundings – as those in the surrounding areas will often want to access the LEZ itself. Indeed, the London low emission zone led to more journeys with cleaner vehicles – also in the neighbouring authorities – as more people were encouraged to switch to compliant vehicles. Sharing impact assessments with neighbouring authorities can help overcome their concerns.

Diversity of users and stakeholders

The socio-economic situation of residents and mobility users can range widely, as can their cultural background and mobility needs (among others). It is particularly important to include those with special needs into any discussions; this might include those on low incomes, people with disabilities or who do not work, especially those who are responsible for caring for dependents.

Age and life stage are also key determinants for mobility needs and behaviours. Combining the mobility needs with age (life stage) and income across the different groups can provide important insights into the needs of these groups, who may not be the most vocal in stakeholder engagement outreach but may end up being the most affected by an UVAR. Another example is migrant communities who may live within or very close to the proposed zone, whose needs may be slightly different from other citizen groups due to language, faith or social norms. Extra effort may be required to reach some hard-to-get-to groups. There are many different categories of user and these need to be set out in the project.

This diversity is one of the key reasons why UVARs will never become a one-size-fits-all solution; what shows great results in one city might show limited or no success in a city with different demographic patterns. This diversity needs to be reflected in the stakeholder outreach. Careful training of the facilitators is also required so that everyone feels able to and encouraged to share their views and perspectives.

While some UVARs only affect some users (e.g., low emission zone for commercial heavy goods vehicles), others (e.g., car-free neighbourhoods or limited-traffic city centres) affect a wider variety of users. The difference in UVARs must therefore also be taken into account when working with a broad range of user groups.

[36] The functional urban area (FUA) is a city and its commuting zone, see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Functional_urban_area

[37] https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/Dynaxibility4CE/UVAR-Topic-Guide.pdf gives guidance on UVARs in the FUA context

4.2.3. Timing of engagement activities

Choosing who to involve and when to do so is important, and will depend on your specific situation. It may be different if you are planning an UVAR based on a number of studies or on a national framework or if you have a specific direction in mind than if you are fairly open to suggestions for an area where early brainstorming with interested stakeholders may be useful. Other factors may include the size or strategic importance of the area or the land use type within the area, as well as how controversial the scheme is likely to be. A common step near the end of the process – even required by law in some cases – is a public consultation on a concrete proposal.

Generally, one would start engagement with different departments inside the authority. When approaching those outside the authorities, approaching those who have expressed interest may be a good place to start – always balanced with the need to get a broad and representative range of stakeholders. In all cases, those involved need to have enough information to be able to make informed decisions and participate.

4.2.4. Engagement tools and tips

There are many ways of interacting with stakeholders, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Smaller meetings enable discussion, while larger ones enable (often one-way) explanations to larger groups; online consultations can be useful for gathering information from large numbers of people, to brainstorm at the beginning, to collect views throughout the process, or for public consultations once the final scheme has been decided and assessed.

Strategies should be developed to include communities that may not be able to attend in-person meetings (especially if they are held in the evening) such as single parents, mothers, people with disabilities and migrant communities. It is important for equity and inclusiveness to ensure that these groups are given suitable opportunities to learn about and understand the project as well as share any views and/or concerns they may have.

Some UVARs only affect some users (e.g., a low emission zone for commercial heavy goods vehicles), while others (car-free neighbourhoods or limited-traffic city centres) affect a wider variety of users. This will affect how the stakeholder engagement process is undertaken.

The ReVeAL project took place during the Covid-19 pandemic, meaning “live” meetings in the partner cities were limited and creativity was needed with online tools and methods for engaging people. This was not all bad. Being forced to rethink old ways can lead to some new and better ones. The expanded use of online participation tools enabled larger numbers of responses and participation by some who otherwise would not have been involved. However, this does not entirely replace face-to-face meetings and discussion and care is needed to ensure that groups who have more difficulty with online options are included in other ways.

There are several different resources on stakeholder engagement, including from CIVITAS[38], C40 and Dynaxibility, as well as tips from Dutch ZEZS on working with the city’s own fleets and working cooperatively at a regional level[39].

[38] e.g. https://civitas.eu/thematic-areas/public-participation-co-creation, https://www.eltis.org/sites/default/files/trainingmaterials/civitas_brochure_stakeholder_consultation_web.pdf, https://www.eltis.org/sites/default/files/trainingmaterials/qf-brochure_participation_en_0.pdf , https://www.eltis.org/sites/default/files/trainingmaterials/guidemaps_volume_1_colour.pdf,

[39] https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1tfcedg2QvayNhh0X-1sarXeUUz0_jixg?usp=sharing

4.3. User needs and public acceptance

Stakeholder involvement is a key part of meeting user needs and achieving public acceptance, as discussed above. If user needs are not taken into account when designing an UVAR scheme, a city may end up with a system that does not work as anticipated. It is important here to distinguish between user needs and user desires. The need may be to access the area, the desire may be to access the area by private car; ensuring the perceived access need is appropriate and an issue that the UVAR should address, but this may not always be in the desired mode.

The stakeholder (section 4.2) and equity (section 4.7) sections address the important issue of making sure the needs of all groups are heard, and the diversity of different needs in a city is one of the reasons why UVARs are not a one-size-fits-all solution. There is a risk that essential transport needs cannot be met or that certain groups will be unintentionally disproportionately affected if stakeholders are not involved. Some user concerns can be addressed, but the supposed automatic “right” to drive everywhere may not.

4.3.1. Public acceptance

Public opinion and acceptance will almost certainly vary across user groups. While it is unreasonable to expect the scheme to please everyone, overall, it is important for any UVAR scheme to have a high level of general local support for it to work well. A scheme that is well designed with stakeholder involvement, tackling a known and agreed-upon problem has good chance of being accepted. Public opinion may vary across societal groups, as will the needs. Furthermore, public acceptance and opposition often fluctuate over time, meaning acceptance should be seen as a continuous process and not a once-and-for-all “for or against” a specific UVAR.

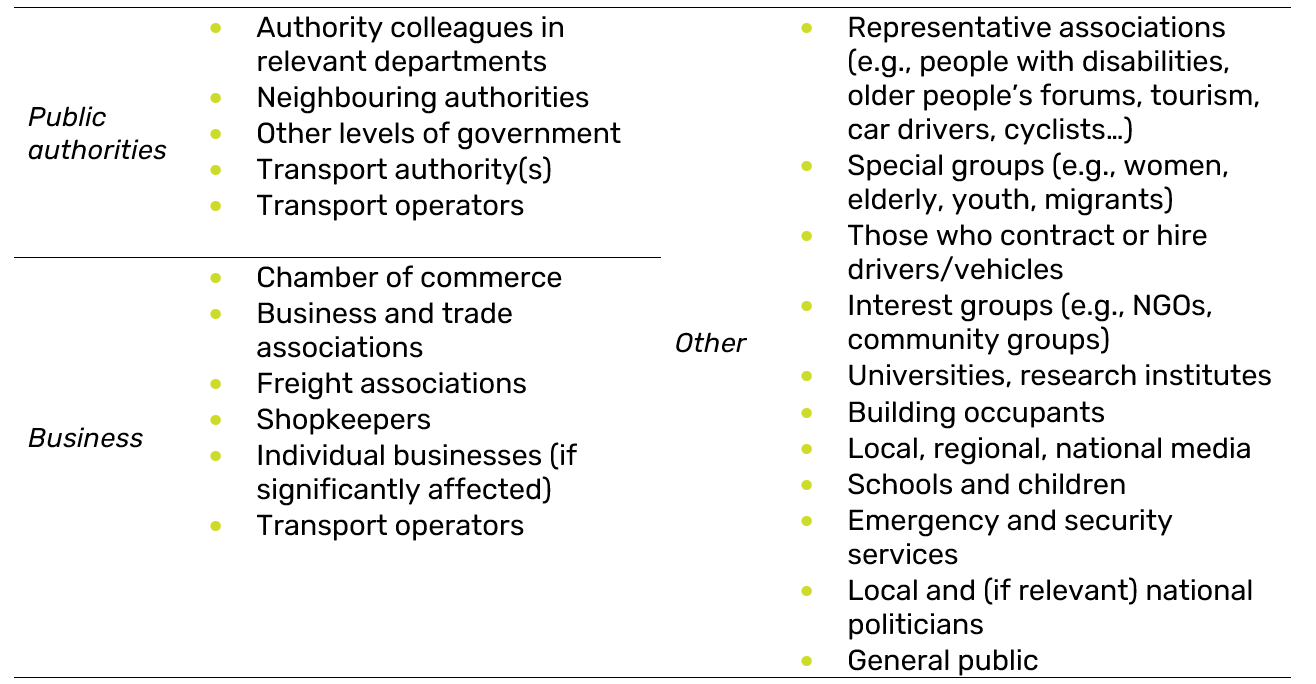

The acceptance curve

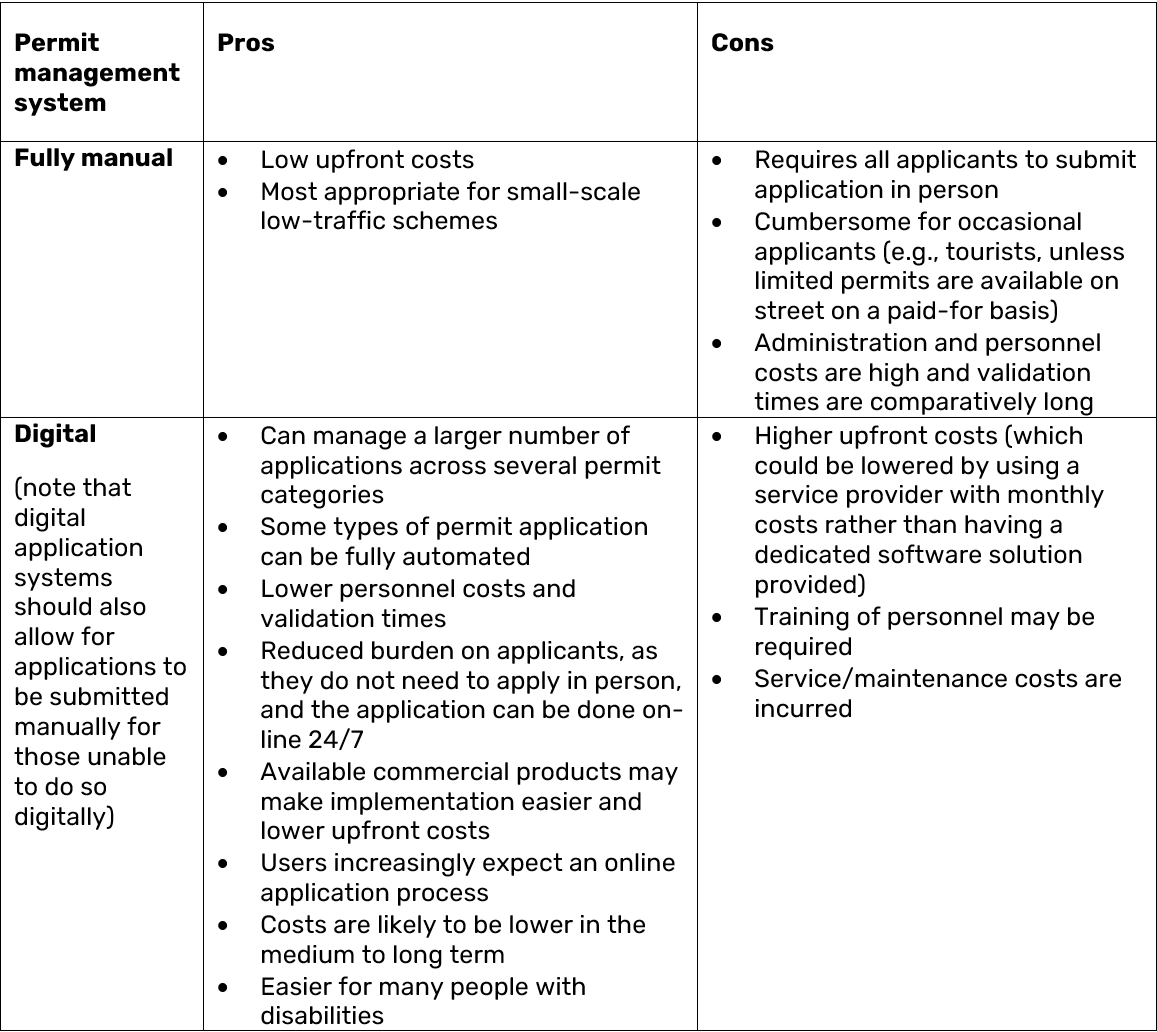

Public acceptance will change over the lifetime of a proposed scheme. As an example, the same distinct pattern of acceptance has been observed in the implementation of congestion charges in several cities (see Figure 6).