European cities are increasingly using UVAR to transition from car-centric mobility systems to more diversified, sustainable, and accessible ones. Is this shift fair, equitable and inclusive? The answer is yes – if UVARs are well-designed.

Air quality as a matter of mobility justice

As Koos Fransen and Lucy Sadler lay out in their article in Thinking Cities, reduced car traffic leads to better air quality. This reduction benefits low-income neighbourhoods – which are disproportionally impacted by high concentrations of health-harming air pollutants; it also favours vulnerable groups (children, the elderly, people with health issues, etc.). CurieuzenAir, a citizen-led initiative in Brussels, found that nitrogen dioxide levels were the highest in the capital’s low-income areas.

As Koos Fransen and Lucy Sadler lay out in their article in Thinking Cities, reduced car traffic leads to better air quality. This reduction benefits low-income neighbourhoods – which are disproportionally impacted by high concentrations of health-harming air pollutants; it also favours vulnerable groups (children, the elderly, people with health issues, etc.). CurieuzenAir, a citizen-led initiative in Brussels, found that nitrogen dioxide levels were the highest in the capital’s low-income areas.

Inclusive UVARs are possible

If designed improperly, UVARs can impact lower-income households who live either further from the city centre or have older cars. However, these can be mitigated through targeted measures to ensure UVARs are inclusive. For example, in Brussels, if you scrap your car, you are eligible to receive a monetary premium called Bruxell’Air that is measured according to your income. It can be spent on a range of mobility services, including public transport passes, shared vehicles, bicycles, and more.

Harmonising measures for a fairer mobility

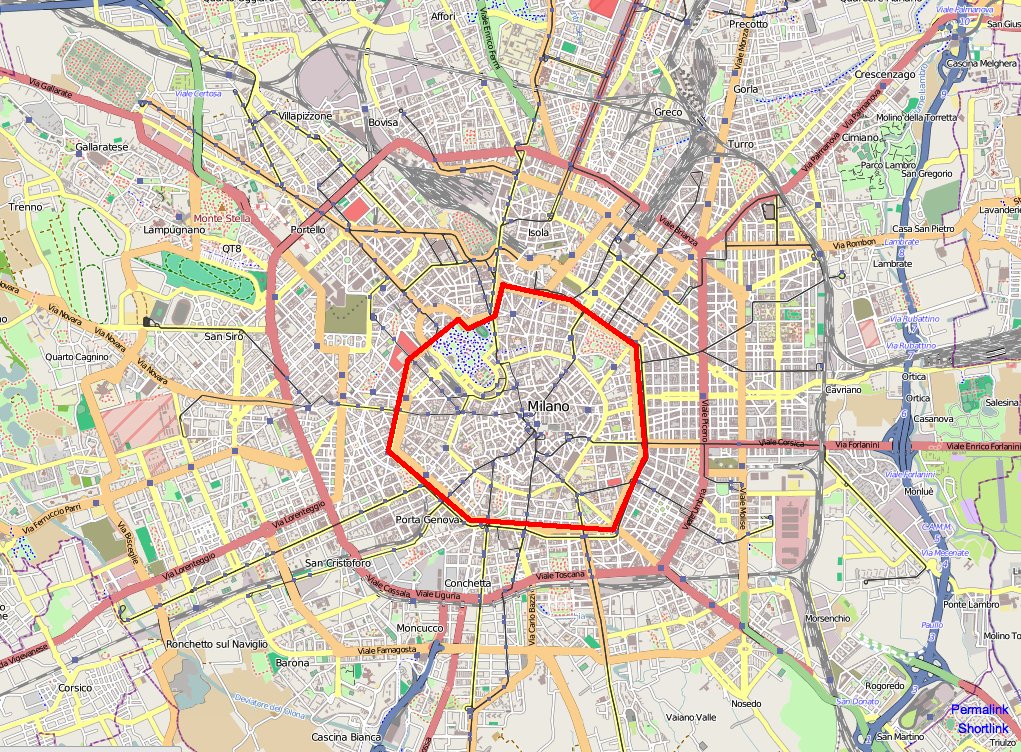

Finally, UVARs are not stand-alone policies. They are put in place by local governments in conjunction with a “package of accompanying or interlinked measures” that improve mobility for all in a cleaner, safer and more inclusive way. When Milan introduced its congestion charge scheme in 2012; the city introduced a range of complementary measures including additional public transport lines and frequencies, upgraded cycling networks, P&R facilities, and free parking for loading and unloading. To find out more, read our UVAR Guidance Mobility Concepts.

Finally, UVARs are not stand-alone policies. They are put in place by local governments in conjunction with a “package of accompanying or interlinked measures” that improve mobility for all in a cleaner, safer and more inclusive way. When Milan introduced its congestion charge scheme in 2012; the city introduced a range of complementary measures including additional public transport lines and frequencies, upgraded cycling networks, P&R facilities, and free parking for loading and unloading. To find out more, read our UVAR Guidance Mobility Concepts.